17.1 Formula for $A^{-1}$

$A^{-1}$ can be given as $A^{-1} = \frac{1}{|A|}C^T$, where $C^T$ is the matrix of cofactors transposed. To verify this formula, we have to check that $AA^{-1}=I$, or $AC^T=|A|I$. If we expand the left hand side, we get

$$\begin{align} \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & … & a_{1n}\\ : & : & :\\ a_{n1} & … & a_{nn} \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} C_{11} & … & C_{n1}\\ : & : & :\\ C_{1n} & … & C_{nn} \end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix} |A| & 0 & 0\\ 0 & |A| & 0\\ 0 & 0 & |A| \end{bmatrix}=|A|I \end{align}$$

17.2 Cramer’s Rule

The solution for the equation $Ax=b$ can be given as $x=A^{-1}b=\frac{1}{|A|}C^Tb$. Different components of $x$ can be given as: $x_1 = \frac{|B_1|}{|A|}; x_2 = \frac{|B_2|}{|A|};…;x_j = \frac{|B_j|}{|A|};…$, where $B_1$ is the matrix $A$ with column 1 replaced by $b$. Hence, $B_j$ is the matrix $A$ with column $j$ replaced by $b$.

17.3 Volume

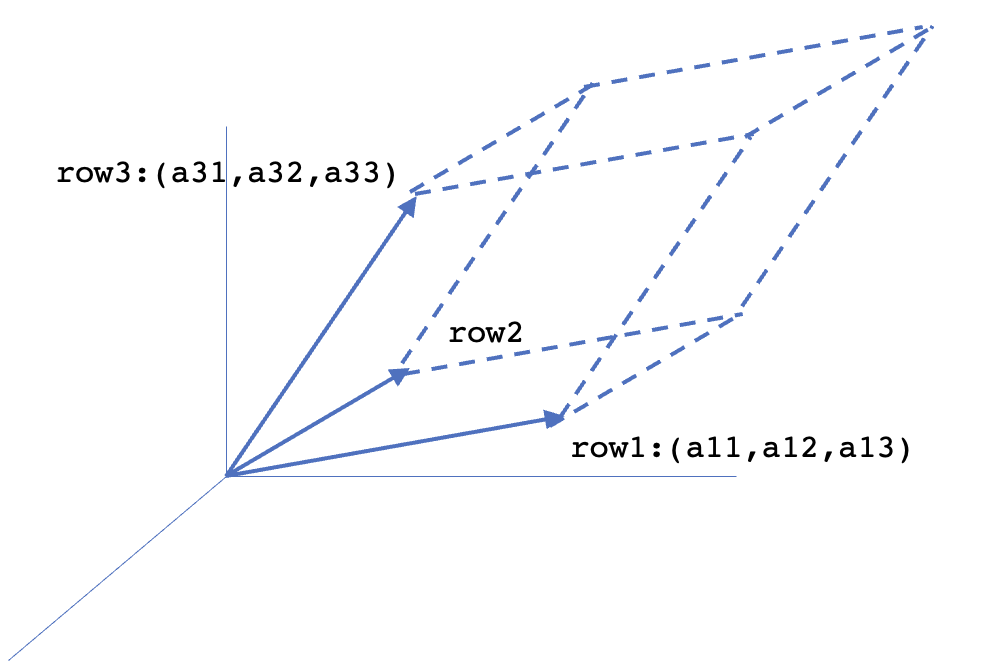

Given a matrix $A$, $|A|$ gives the volume of a box or to be specific a parallelopiped. One thing to note the fact that $|A|$ can be negative. We can take the modulous to represent the volume instead. The parallelopiped represented by matrix $A$ is shown below.

For the identity matrix $I$, the box is a unit cube and the statement holds true. For orthogonal matrix $Q$, the formed box is a unit cube rotated by some angle in the space. For the matrix $Q$, we have $Q^TQ=I$. Taking determinant of both sides, we get $|Q^T||Q|=1 \implies |Q|^2=1 \implies |Q|=\pm 1$. Hence, for orrhogonal matrices as well, the determinant equals the volume of the box.

One of the important property to note is let’s say we double one of the edges of the box. This will double the volume. Doubling the edge means multiplying one of the rows by $2$ which doubles the determinant of the matrix as well. Hence, the volume satisfies the property 3a (discussed in Chapter 15).

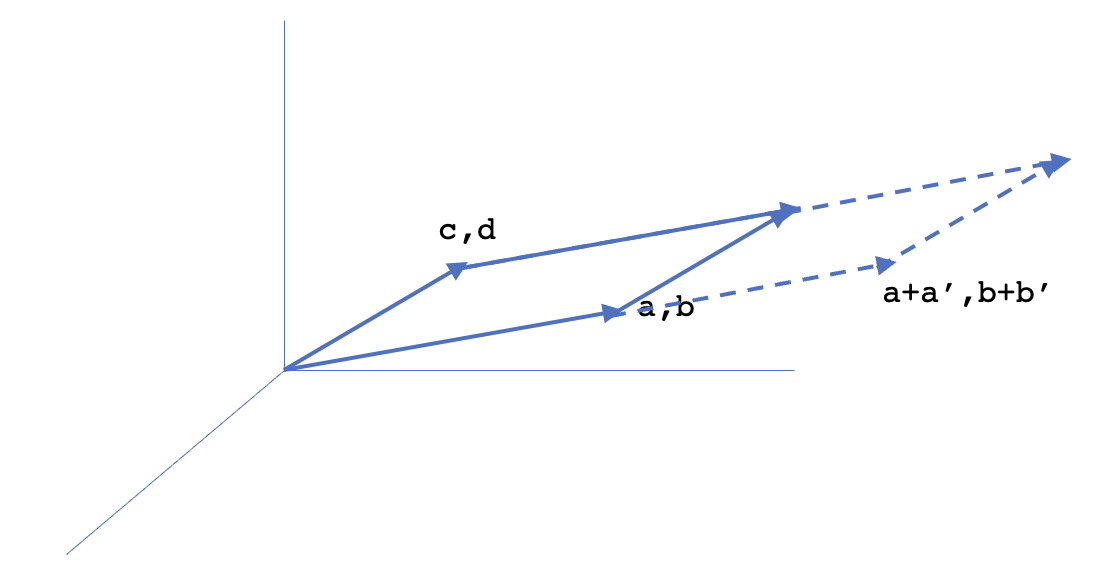

Property 3b says that, for any square matrix $A$, $|A|$ behaves like a linear function of a row if all the other rows are keep fixed, i.e. $\begin{vmatrix} a+a^{’} & b+b^{’} \\ c & d \end{vmatrix}=\begin{vmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{vmatrix}+\begin{vmatrix} a^{’} & b^{’} \\ c & d \end{vmatrix}$

If we look at the above $2 \times 2$ matrix, it represents a parallelogram shown below. The bigger parallelogram is represented by the matrix in the left hand side and two smaller parallelograms are represented by two determinants on the right hand side. Hence, the statement about volume follows the property 3b as well.

One last thing to note is the fact that for all the cases and examples, we have taken the boxes whose one of the vertices is at origin. If we have a box whose none of the vertex is at the origin, we can shift it to the origin and calculate the volume/area by computing the determinant.